Communiqué 53: When the artifacts come home to roost

Stolen African artifacts are returning to the continent en masse. This creates new massive opportunities for the creative economy. But how will African countries handle them?

1. A tale of two museums

Every November, Lagos transforms itself from Nigeria’s commercial capital to its cultural capital. The hustle and bustle of the financial district give way to art exhibitions and cultural festivals, from Art X to the African International Film Festival. But last year, things were a bit different. While the festivities were happening in Lagos, the ancient city of Benin hosted one of the most significant events in Nigeria’s arts and culture.

The Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) was previewing its purpose-built building. The two-day event, titled Museum in the Making, featured the building’s hard hat opening, creative workshops, panels, and social gatherings. Marking the start of the museum's first annual programming season, it led up to MOWAA’s inaugural exhibition, which will be held later this year.

Thousands of miles away in Egypt, the Grand Egyptian Museum had opened the doors of some of its galleries for a trial run of 4,000 visitors. The museum, near the Pyramids of Giza, will showcase more than 100,000 Egyptian artifacts, including treasures from the tomb of King Tutankhamun. The billion-dollar museum, initially scheduled to open in 2012, had suffered repeated delays due to political turmoil, cost overruns, and the COVID-19 pandemic, but was now finally preparing for its opening.

Both museums had something in common; at their inaugurations, they showcased expansive collections of traditional African art, a significant part of which had been repatriated to the continent in recent years. But their openings also marked a new chapter in a decades-long movement.

2. A long way home

The movement for repatriating African artifacts to the continent has been gathering steam for years. It represents a significant shift in global cultural relations between the continent and the rest of the world. These artifacts—most of which were taken during the colonial era through looting, forced sales, or duress by European powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—hold deep cultural, spiritual, and historical significance for their communities of origin.

The growing momentum for restitution is a result of the continued efforts of African nations that have long campaigned for the return of these priceless artifacts. Countries like Nigeria, the Republic of Benin, and Ethiopia have been at the forefront of the movement, and their efforts have begun to yield results. In 2022, the Smithsonian Museum returned 29 Benin bronzes to Nigeria. More recently, the German government handed over a cache of 22 artifacts to Nigeria. In total, 117 African artifacts were publicly returned to the continent in 2024.

Also, Western countries that hold these artifacts have increasingly begun to recognize that retaining them raises serious ethical concerns. In 2020, France passed critical legislation paving the way for the return of artifacts to the Republic of Benin and Senegal. The repatriation movement has sparked changes in museum policies and national laws across Europe and beyond.

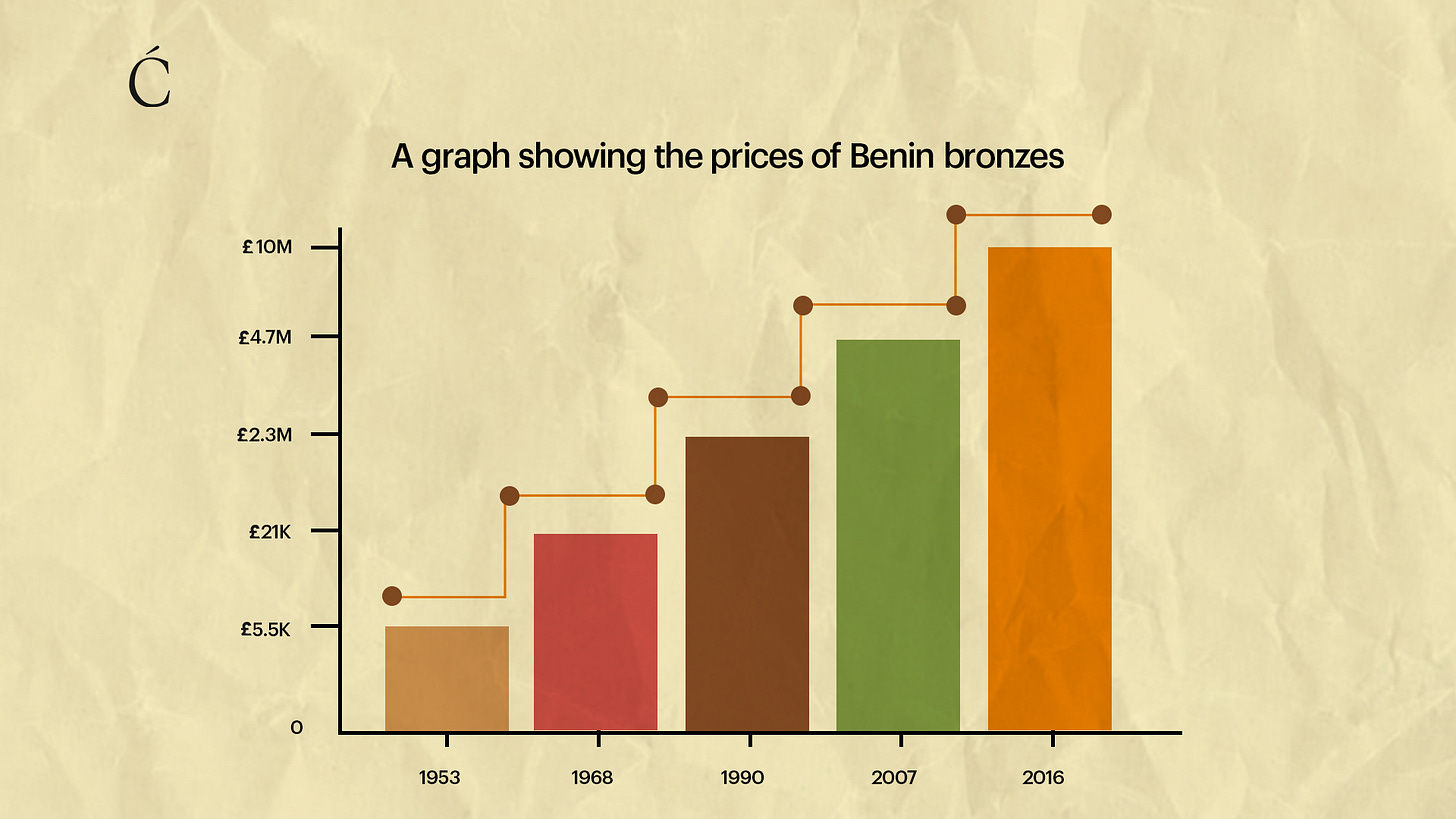

But beyond the cultural importance of repatriation, there’s also an economic significance. Africa's art market is valued at $1.8 billion, with classical art pieces like the Benin bronzes underpinning this market. A 2021 report on the African art market found that 96% of collectors preferred to collect classical art pieces, while only 20% preferred newer contemporary pieces. However, this is just a small fraction of the $65 billion global art market.

The African art market could be larger, but a significant percentage of the value is captured outside the continent. For instance, when the Ohly Head, one of the looted Benin Bronzes, was sold for $10 million in 2016, none of the proceeds went to Nigeria. The British Museum, which houses 200,000 African art pieces, received over five million visitors and generated £11 million for the British government in 2023. Unsurprisingly, the British Museum has held on to its collection, refusing to return any of the artifacts but instead opting to lease them back to their home countries.

3. Rules for return

There have been several attempts to create an international framework for the repatriation of artifacts, the most significant of which was the 1970 UNESCO convention on the means of prohibiting and preventing the illicit import, export, and transfer of ownership of cultural property created the first guidelines for the repatriation of cultural artifacts. This was followed by the 1995 UNIDROIT convention that required the return of illegally exported or excavated cultural objects. It went on to define cultural objects as those that are important for art, history, literature, science, archaeology, or prehistory.

However, these conventions failed to have the required effect. Both were not retroactive, meaning that they took effect from the time they were enacted and did not cover artifacts that had been looted before then. Also, most of the signatories to the conventions are countries in the global south. Western countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, where most of these artifacts reside, have refused to ratify these conventions to date. Instead, some countries including Germany, Netherlands, and Belgium have set up individual national guidelines to process artifact claims.

4. Maximizing the return

For the most part, discussions about repatriations have focused on what Western countries and institutions are doing to return wrongfully acquired artifacts back to their home countries. Those discussions have yielded results and the artefacts are coming home.

African nations can best utilize them by:

Digitizing the artifacts: African countries can maximize the value of repatriated artifacts by using digital technology to make these treasures accessible to a global audience. This includes creating high-quality digital replicas, 3D models, and virtual tours, ensuring cultural treasures can be experienced and appreciated worldwide, even by those unable to visit the physical locations. A notable example African nations can emulate is the Smithsonian Institution’s Open Access Initiative, which offers free digital access to millions of cultural assets, including 3D scans of artifacts. This has expanded the Smithsonian's audience and encouraged innovative uses of its collections, such as virtual reality experiences and academic research. African museums could adopt similar open-access policies for digitized artifacts, enabling scholars, artists, and cultural enthusiasts worldwide to engage with their collections. Work has already begun in Nigeria, with the launch of the Digital Benin project, an online database of Benin Bronzes held by museums across the world.

Cultural tourism: African nations can design their tourism strategy around the returned artifacts. Beyond just displaying these artifacts in the museum, countries can create immersive experiences by taking tourists through the historical sites where the artifacts were gotten from. For instance, when visiting the Acropolis Museum, which houses artifacts from ancient Greece, tours go beyond the museum to local artisan workshops, traditional tavernas, and contemporary art galleries. This provides visitors with an understanding of how ancient Greek culture influences contemporary life. African countries could adopt similar strategies by linking repatriated artifacts to cultural sites and festivals. For example, Nigeria could showcase some of the returned Benin bronzes in The Museum of West African Art paired with tours of the ancient Benin Kingdom’s historical sites like the Oba's Palace and the Ancient Benin Walls.

Creative industry stimulation: Returned artifacts can serve as creative resources that contemporary artists tap into in creating new artworks. But first, the artists have to understand the history around these artworks, and that's where education programs come in. The key here is to create a supportive ecosystem that helps artists translate cultural heritage into contemporary creative products while maintaining cultural authenticity. For instance, the Benin Bronzes could teach about pre-colonial African societies and their achievements. They can also be used in STEM education, showcasing the sophisticated engineering of the Bini civilization. An example of this strategy in practice is Nigerian musician Rema, who wore a replica of the Queen Idia mask during his 2023 performance at the O2 Arena, incorporating traditional Bini culture into his art. The key here is to create a supportive ecosystem that helps artists translate cultural heritage into contemporary creative products while maintaining cultural authenticity.

5. Bottom line

One of the major arguments Western countries use to justify holding on to looted African artifacts is that African countries cannot properly manage these artifacts when they receive them, and even though it is not the place of these Western countries to determine how well Africa manages its artifacts, there is some truth to this assertion.

In 2021, France returned 26 looted artworks to the Benin Republic. In 2022, Benin Republic held a temporary exhibition for the pieces, attracting over 200,000 visitors in just a few months. But since then the artworks have been off limits to the public, locked away in a storage room in the country’s presidential palace, awaiting the completion of museums to display them.

The fact is that a lot of African countries cannot yet handle the artifacts that are being returned to them. But what is important is that ownership of these artifacts is transferred to their rightful owners. Then while African countries are developing the capacity to properly utilize the artifacts, the artifacts could go on tours to other countries or even remain in the countries that took them, helping raise revenue and international awareness of their home countries. Initiatives like MOWAA and the Grand Egyptian Museum, are laudable but there is still a lot of work to be done on the part of the African countries requesting these artifacts.