Communiqué 102: Substack lost its way

How venture capital and creator economics diluted Substack’s original promise to writers.

1. The platform that once was

On Thursday, Substack announced it was launching “the Substack TV app for Apple TV and Google TV.” It also called itself “the home for the best longform…work.” If you haven’t been following Substack from the beginning, that statement might not stand out.

But my heart sank after reading the post. It was such a far cry from what Substack initially promised that I had to leave this comment:

“Interesting. You guys have gone from saying Substack is the best home for longform writing/writers to ‘Substack is the home for the best longform—work….’ I get trying to evolve, but this just seems like another venture capital-fueled idea. Reminds me of Medium all over again. Another one bites the dust, it seems. Heh.”

The TV app is the latest in the slew of new features Substack has introduced in the last four years. Its initial premise was simple: to be the best place for long-form writing and give writers a home from which to build their businesses. It did this first by providing an easy-to-use platform for publishing and newsletter community-building. (That’s what motivated me to launch the Communiqué newsletter here.) Then it introduced financial incentives in the form of insurance and legal support for a handful of writers (particularly journalists). But most of all, Substack’s cofounder, Hamish McKenzie, postured heavily as the guy who cared about writers. In fact, his designation at the company is “Chief Writing Officer.”

In 2019, Substack introduced podcast features, but they were still designed to enable writers and publishers to reach new audiences through new formats.

The big changes began in 2022 when it launched video features. But even still, those were designed for writers, with the same goal of reaching new audiences. One of the product tutorial posts read, “At Substack, we believe great writing is valuable. We’re focused on building simple tools that allow you to grow your audience and earn an income directly from subscribers, on your own terms. Learn about the new tools we’ve built with writers below.”

In 2023, however, the tone and focus shifted from “writers” to “creators,” and it was then that the promise began to fade. This coincides with the global rise of “creator economy” narratives. Substack, with its Notes app and other features, became more inclined towards social media publishing and competing with the Twitters (or Xs, for those who choose to call it that) and Facebooks of this world than catering to the writers and journalists it once courted.

And so, today, Substack is looking to be the next big destination for creators, hoping to eat bigly into the creator economy pie. It is no longer the platform it once was.

2. Kool-Aid with no sugar

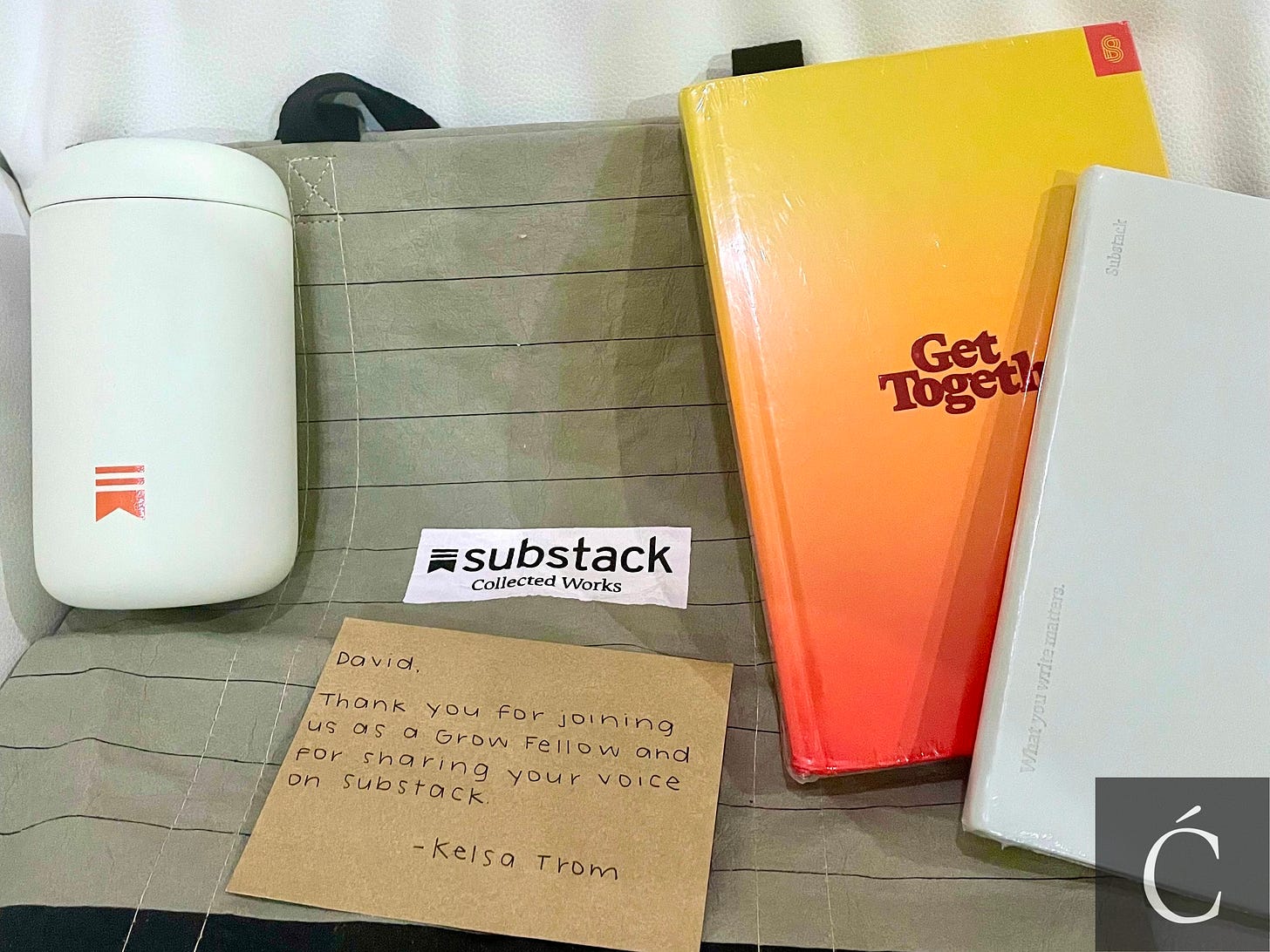

In November 2021, I got into the Substack Grow Fellowship, one of 11 fellows from across the world. It was a blissful experience, for me at least. We got business and strategic support, mentorship, and, most importantly, financial backing to grow our publications. We also interacted often with members of the Substack team.

On at least one occasion, we talked directly with Hamish McKenzie. I sensed that the platform was deeply committed to the future of writing and publishing as both an art form and an economic lever. We were encouraged to use the fellowship to future-proof our “writing” and “publication.” Again, the messaging was very clear about what Substack wanted to accomplish.

All that has since changed, and it is understandable. The company has raised over $200 million in funding and is now valued at about $1.1 billion. Of course, it has to justify its valuation to its funders, and it has chosen to shift its focus to “accommodate” more people in the creator ecosystem.

Once you raise venture capital, you no longer control your destiny. You invite an army of cooks into the kitchen, and the broth will only be as sweet or manageable as how many hands you can stop from stirring the pot.

Of the 11 fellows in my cohort, three have moved off Substack, and one no longer publishes. My mentor during the fellowship, Casey Newton, has also left the platform and moved his publication Platformer to Ghost. Perhaps this should have been the strongest signal for me, given that Casey was one of Substack’s earliest champions and support beneficiaries. For him to have left the platform so strongly and publicly as he did, I should have sensed what was coming.

Well, now I do. It is clearer than ever. Substack’s primary focus is no longer on writers, and while that is fine (it is their prerogative, after all), it is disheartening.

Venture capital cannot accommodate writing as both an art form and a business. Perhaps this is the sign of the times we live in. The world has become more visual, and audiences have been trained to accept this as the norm.

3. The great rebundling

Substack helped unbundle media. That was its great contribution. It positioned itself as a home for serious, independent long-form writing at a time when the internet was actively hostile to depth. When everything was optimised for speed, virality, and dopamine hits, Substack made a different bet: that there was still an audience willing to slow down and read.

That belief showed up in the fellowships it funded. It showed up in the people it elevated. It showed up in the kind of work it celebrated, work born of craft, consistency, and intellectual ambition.

But unbundling was never the end state. It was only a correction. What Substack—and the broader independent media ecosystem—has likely realised is that most people will not pay for dozens of individual newsletters indefinitely. Not because the writing is bad, but because their attention is finite and subscriptions quietly pile up until they feel less like patronage and more like clutter. This is where the rebundling begins.

There will be a return, not to old media institutions, but to something looser and more adaptive: individual writers growing into small media companies, collectives, or tightly curated networks with shared subscriptions and overlapping audiences. We are already seeing this, and we will see much more of it in the coming years.

4. Lost in the noise

As platforms like Substack scale, they will always choose the categories that grow fastest. Today, that category is not writing; it is the creator economy.

Substack’s evolution is not just about venture capital or product expansion. It is a signal of something more consequential: writing is being swallowed whole by the broader creator economy, flattened into just another “content format” alongside video, audio, and social posts.

And that should give us pause.

I say this as someone who believes deeply in the creator economy and studies it closely. I understand its power and its role in dismantling old power structures. But I am a writer first. And writing is not merely another content vertical. It is a discipline and a craft that does not survive well when reduced to engagement metrics and surface-area growth.

The evidence is already visible. When most people hear the word creator today, they do not think of writers. They think of videos. Maybe even podcasts. They think of feeds and formats optimised for platforms that reward immediacy over reflection. Writing, by contrast, demands slowness, both from those who produce it and those who consume it.

When writing loses its status as a core pillar of this industry, it does not simply get “outperformed.” It gets deprioritised, and then marginalised, treated as a nice-to-have, a supporting act.

This is the quiet risk embedded in Substack’s shift. Not that it is expanding, but that in expanding, it is signalling that writing alone is no longer enough. And in doing so, it reminds writers of an uncomfortable truth: if the future of writing is left entirely to platforms optimised for creators, the art form itself will continue to shrink in importance.

Preserving writing—serious, long-form writing—will require more than tools. It will require structures, incentives, and institutions that don’t just treat it as content. That work, inconvenient as it may be, cannot be outsourced.

PS: I fully recognise the irony of publishing this essay on Substack. Despite all its broken promises, I still like it here. For now, at least.

100% agree & one of the reasons why I really enjoyed writing & being on Substack was to get that depth in thought, research, and writing. However, as with all the many choices founders & organisations face, finding that right balance to preserve your “why” and still keep the business afloat and progressive is very important.

Also, I generally look at these things as experimentation - trying & seeing if it works? LinkedIn discontinued stories (I mean who wanted stories on LinkedIn?!), IGTV also didn’t stick initially but reels are here. Curious to see how this plays out, the uptake and what the learnings will be.

Perhaps, we can revisit this essay in future.

Whenever I watch shows like Star Trek and read books like Iain Bank’s The Culture series, I find it so fascinating that in those stories, real physical books are treated as relics. It always seemed crazy to me that writing as an art form would one day become lost to humanity.

Substack’s rise to me also felt the same. It felt like there was still hope for readers. In between books and tweets there’s essays.

The weirdest thing about human beings is the way we’ve been trained. Getting people to watch videos just happened to be the best way to keep them staring at a screen long enough to show them ads. Somewhere along the line writing/publishing became harder and harder to sustain because humans now want fast flashy videos.

The score is Capitalism 50. Writing 2.